At sunrise, Jaipur’s terracotta facades come alive in soft light, revealing a city that’s not only beautiful but brilliantly designed. Conceived in 1727 by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II and brought to life by architect Vidyadhar Bhattacharya, Jaipur stands as one of India’s earliest planned cities, a living testament to how thoughtful urban planning can create both structure and spirit.

In this blog, we’ll explore how Jaipur’s centuries-old design principles, from its intelligent grid and climate-sensitive architecture to its vibrant pink facades and inclusive neighbourhood planning, continue to influence cities and designers across the world today.

Ancient Math, Modern Logic

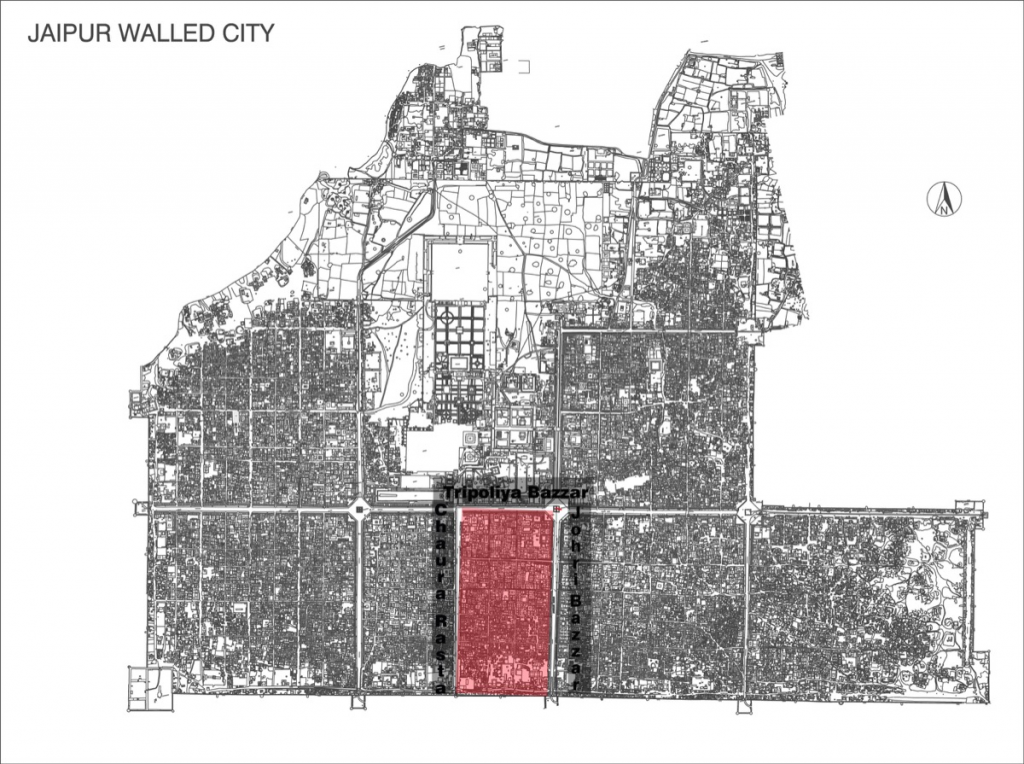

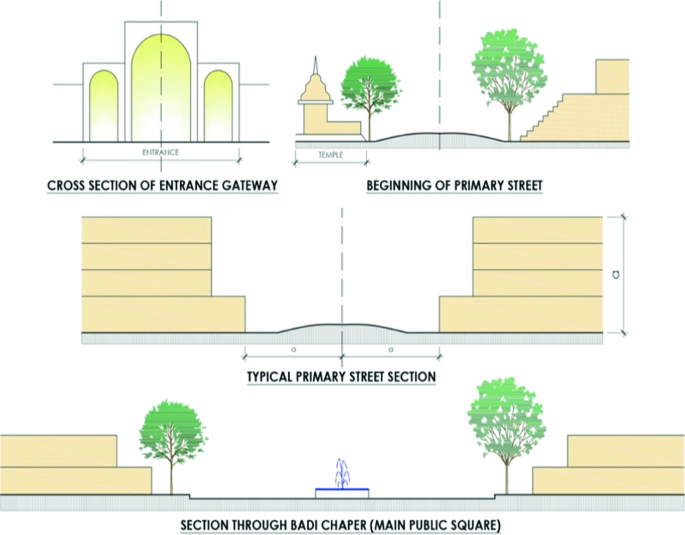

Jaipur’s city plan was based on a nine-square grid, inspired by the ancient science of Vastu Shastra. Each block was carefully organised with wide main roads intersecting at right angles, smaller streets radiating outward, and civic spaces placed at intersections.

This wasn’t just geometry for geometry’s sake. The grid allowed for easy navigation, modular growth, and efficient zoning. Its hierarchical street system, from grand 111-foot boulevards to intimate 27-foot lanes, anticipated modern ideas of traffic flow and neighbourhood structure.

Contemporary planners are rediscovering this logic. Cities like Barcelona, Portland, and Singapore use similar grid systems to promote walkability, reduce congestion, and create neighbourhoods that evolve without losing coherence. Jaipur’s grid reminds us that structure can be the foundation for flexibility, not its enemy.

Climate Design Centuries Ago

Long before “sustainability” became a design mandate, Jaipur integrated climate-responsive strategies into its planning. Streets were oriented to minimise harsh sun exposure, while the ratio between building height and street width was calculated to ensure shade throughout the day.

Continuous facades along major roads created shaded arcades, and courtyards inside homes promoted natural ventilation, a system of passive cooling still admired today.

Modern architects are reinterpreting these lessons through shaded streetscapes, green corridors, and “urban canyon” design, where proportions of streets and buildings control microclimate. What we call climate-smart urbanism today, Jaipur practised intuitively centuries ago.

Chaupars: The Original Multi-Use Urban Squares

At the heart of Jaipur’s grid are the chaupars — large public squares that functioned as markets, meeting places, and cultural venues. Each had a distinct identity: one specialised in textiles, another in jewellery, and others in food or crafts. This multi-functionality made the chaupars social and economic anchors, spaces that connected trade, governance, and everyday life.

Today, as cities invest in plazas, parks, and pedestrian hubs, they’re echoing what Jaipur achieved naturally. Copenhagen’s Superkilen or Melbourne’s Federation Square mirror the same philosophy: flexible spaces that invite people to gather, interact, and celebrate. Jaipur’s chaupars prove that good public space is timeless when it’s designed for people first, not cars or commerce.

Building Identity Through Design

Jaipur’s signature pink colour wasn’t part of its original plan. In 1876, Maharaja Ram Singh ordered the entire city painted in terracotta to welcome the Prince of Wales. What began as hospitality became identity, creating a unified aesthetic that still defines Jaipur today.

That single design decision offers an enduring lesson in urban branding. From Santorini’s whitewashed houses to Santa Fe’s adobe tones, cities use visual coherence to tell their story. Jaipur did it first using architecture to express culture, pride, and belonging.

The Art of Proximity

Each mohalla (neighbourhood) in Jaipur was a self-contained ecosystem. Residences sat above shops, temples, and wells were within walking distance, and craft workshops thrived alongside homes. This vertical and horizontal mix made communities walkable and socially vibrant.

Modern urbanists call this the 15-minute city, where work, living, and leisure are accessible without long commutes. Jaipur achieved it centuries ago. Compact neighbourhoods that encouraged interaction, reduced dependency on transport, and fostered economic diversity.

For contemporary planners, Jaipur’s mixed-use neighbourhoods are a reminder that sustainability is as much about social design as environmental performance.

Ancient Blueprints for Modern Water Resilience

Built in an arid region, Jaipur’s success depended on water management. Its planners integrated stepwells (baolis), rainwater channels, and tanks that harvested and reused water efficiently. The city’s proximity to natural water bodies like Jal Mahal was not accidental; it was strategic.

Today’s Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) frameworks, seen in cities like Singapore or Copenhagen, are rediscovering similar systems under modern terminology — decentralized water storage, blue-green infrastructure, and urban wetlands. Jaipur’s legacy shows that traditional knowledge still holds solutions for contemporary resilience challenges.

For students of architecture and urban design, Jaipur is a living studio. At ARCH College of Design & Business, learners are encouraged to engage directly with the city’s layered history, spatial intelligence, and cultural fabric. Through studio projects, city walks, and research-based learning, students explore how traditional planning principles can inspire innovative, sustainable urban solutions.

Studying in the heart of the Pink City gives aspiring designers a rare advantage: the chance to experience timeless urban design first-hand while reimagining it for a rapidly changing world. ARCH nurtures this spirit of inquiry, empowering future architects and urban thinkers to blend heritage, technology, and human-centred design in shaping tomorrow’s cities.